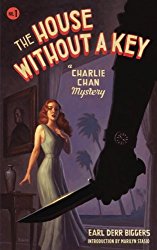

The House Without a Key --

The first Charlie Chan novel

|

There was, she [Minerva Winterslip] noted, an imposing lock, but the key had long since been lost and forgotten. Indeed, in all Dan's great house, she could not recall ever having seen a key. In these friendly trusting islands, locked doors were obsolete. |

The House Without a Key is the book that started the entire Charlie Chan phenomenon. This includes the six novels by author Earl Derr Biggers (and, later, several pastiches by other writers), the more than forty-five movies, the old-time radio shows, comic books and a daily strip cartoon, the television show in the 1950s, the animated Hanna-Barbera television show in 1972, and the final two movies in the 1970s and 1980s.

|

Click Image to Click the image below to |

The Hawaiian islands have a charm about them that is

legendary. A number of people who have visited became so enchanted that they

decided (sometimes on the spur of the moment) to stay and live there. The House Without a

Key—the first Charlie Chan novel—begins with Miss Minerva Winterslip from

Boston, Massachusetts, visiting two cousins of hers who have lived in Honolulu

for years. She intended to visit for six weeks, then return to her hometown.

Now, however, it has been ten months and she shows no indication that she is

ready to return. |

Dan and Amos Winterslip have lived on the islands for decades.

In addition to being brothers, they are neighbors and live on adjacent plots of

land on the beach. Dan is very wealthy and lives in a mansion; Amos is the

opposite—not much money, “oblivious to beauty,” and, although he hasn’t been

East of San Francisco on the Mainland, Minerva sees him as “the New England

conscience in a white duck suit.”

The "Spite Fence"

Although they are brothers, Dan and Amos have not spoken to

each other in decades. Their properties are separated by a barbed-wire fence,

which is known as “the spite fence.” Amos believes that Dan became rich by

unethical and illegal means which cast a scandalous shadow on the Winterslip

name. And the Winterslips, being Boston Brahmins, want to preserve the

integrity of the family name.

|

"Amos!" cried Miss Minerva sharply. He moved on, and she followed. "Amos, what nonsense! How long has it been since you spoke to Dan?" He paused under an algaroba tree. "Thirty-one years," he said. "Thirty-one years the tenth of last August." "That's long enough," she told him. "Now, come around that foolish fence of yours, and hold out your hand to him." "Not me," said Amos. "I guess you don't know Dan, Minerva, and the sort of life he's led. Time and again he's dishonored us all—" "Why, Dan's regarded as a big man," she protested. "He's respected—" "And rich," added Amos bitterly. "And I'm poor. Yes, that's the way it often goes in this world. But there's a world to come, and over there I reckon Dan's going to get his." |

The "Wandering Winterslips"

Some of the more adventurous of the Winterslips have

travelled parts of the world to seek their fortunes and have developed a

reputation for being “the wandering Winterslips.” As Amos puts it, "It's a strain in the

Winterslips. . . . Supposed to be Puritans, but always sort of yearning toward

the lazy latitudes."

But the more conservative nucleus family, back in Boston,

becomes concerned that Miss Minerva has not returned and may be becoming

enchanted with the islands herself. They dispatch a young man of the

family—John Quincy Winterslip—to talk sense into her and to retrieve her.

Biggers writes:

|

In a moment Miss Minerva came again into the room. She carried a letter in her hand, and she was laughing. "Dan, this is too absurd," she said. "What is?" "I may have told you that they are getting worried about me at home. Because I haven't been able to tear myself away from Honolulu, I mean. Well, they're sending a policeman for me." "A policeman?" He lifted his bushy eyebrows. "Yes, it amounts to that. It's not being done openly, of course. Grace writes that John Quincy has six weeks' vacation from the banking house, and has decided to make the trip out here. 'It will give you some one to come home with, my dear,' says Grace. Isn't she subtle?" "John Quincy Winterslip? That would be Grace's son." Miss Minerva nodded. "You never met him, did you, Dan? Well, you will, shortly. And he certainly won't approve of you." "Why not?" Dan Winterslip bristled. "Because he's proper. He's a dear boy, but oh, so proper. This journey is going to be a great cross for him. He'll start disapproving as he passes Albany, and think of the long weary miles of disapproval he'll have to endure after that." |

Although the text refers to him a number of times as “the

boy,” John Quincy Winterslip is twenty-nine years old. He is a world traveller

himself and has been to Europe a number of times. He loves Paris.

But John Quincy has never travelled to the western part of

the United States before. Arriving in San Francisco by train, he has the

uncanny experience of feeling that it is very familiar to him and that he has

been there before. In San Francisco, John Quincy Winterslip has a sense that he

is home.

Continuing his journey to Honolulu John Quincy embarks on the

ship called The President Tyler. There he meets his cousin—Dan’s daughter,

Barbara, who is with her fiance Harry Jennison.

The boat arrives just outside of Honolulu during the

night-time. There is a protocol for docking and they have arrived after hours

and must remain anchored overnight. While John Quincy and Barbara are waiting

offshore, Dan Winterslip is murdered at his mansion in Honolulu. John Quincy and

Barbara learn of the murder the next morning after they pull into port and

disembark.

Charlie Chan Is Conceived

There is quite a bit of backstory before we are introduced

to Charlie Chan. According to accounts, Biggers had written a draft of the

novel which did not include Chan. Several years later, Biggers came across a

newspaper article about Chang Apana, a Chinese man who had worked for the

Honolulu police department for decades. The concept of a Chinese man as a hero

detective became the inspiration for the character of Charlie Chan.

Biggers worked Chan into the book but may well have been

unsure whether a Chinese detective would be accepted by his readers as the

hero. Chan didn’t appear until chapter 7. At the time of writing this first

Chan novel, Biggers could have no idea of the huge success Charlie Chan would

become.

The House Without a Key Is a Classic Whodunnit

|

Click Image to Click the image below to |

Earl Derr Biggers is a master of plot, and The House Without a Key is a “whodunnit” in the classic sense of detective, crime, and murder mystery books published during the beginning of the genre’s “golden age.” Some characters and suspects include:

|

Introducing Charlie Chan

In spite of accurate observations that Charlie Chan was not

representative of authentic Chinese customs, traditions, and beliefs, Chan was

a tremendously likeable character and the books (and movies that followed) went

a long way to improving relations between Western readers and Chinese people

during a time when suspicions, prejudices, and racial biases were prevalent.

The First Description of Charlie Chan Anywhere

The first description of Charlie Chan—not only in this book

but anywhere—occurs in Chapter VII:

|

As they went out, the third man stepped farther into the room, and Miss Minerva gave a little gasp of astonishment as she looked at him. In those warm islands thin men were the rule, but here was a striking exception. He was very fat indeed, yet he walked with the light dainty step of a woman. His cheeks were as chubby as a baby's, his skin ivory tinted, his black hair close-cropped, his amber eyes slanting. As he passed Miss Minerva he bowed with a courtesy encountered all too rarely in a work-a-day world, then moved on after Hallet. "Amos!" cried Miss Minerva. "That man—why he—" "Charlie Chan," Amos explained. "I'm glad they brought him. He's the best detective on the force." "But—he's Chinese!" "Of course." |

Charlie Chan's Traits

Charlie's Physical Traits

In addition to Charlie Chan’s physical traits, described

above, other traits give us a more complete picture of the man.

Charlie's Language Traits

Chan speaks English reasonably well, although often not

quite grammatically correct. Words and phrases such as the following pepper his

speech: “Undubitable” instead of “indubitable”; “unadvisable”; “unsignificant”;

“It are unevitable”; “It are not the message here”; “Patience are very lovely

virtue”; and the like.

Also, influenced by his cousin Willie Chan, Charlie occasionally

lapses into American slang and uses phrases such as “Hot dog!”

But Chan wants to improve his knowledge and use of proper

English. In Chapter XVI, he says, “Endeavoring to make English language my

slave. . . . I pursue poetry."

In a number of the Charlie Chan novels, Chan speaks

Cantonese, which is a dialect.

Charlie Is Patient and Polite But Can Be Assertive

As Biggers describes Chan throughout the novel we see that he is always polite and frequently patient. But when he needs to be assertive and authoritative he can be, as the following passage from chapter XV illustrates:

|

"I am Detective-Sergeant Chan. Honolulu police. You will do me the great honor to accompany me to the station, if you please." Brade stared at him, then shook his head. "It's quite impossible," he said. "Pardon me, please," answered Chan. "It are unevitable." "I—I have just returned from a journey," protested the man. "My wife may be worried regarding me. I must have a talk with her, and after that—" "Regret," purred Chan, "are scorching me. But duty remains duty. Chief's words are law. Humbly suggest we squander valuable time." "Am I to understand that I'm under arrest?" flared Brade. "The idea is preposterous," Chan assured him. "But the captain waits eager for statement from you. You will walk this way, I am sure. . . ." |

Charlie Is Self-Deferential

When John Quincy Winterslip visits Chan’s home (in chapter

XIX), Chan says, “You do my lowly house immense honor.”

When introducing his son, Henry, Chan tells John Quincy,

“Kindly condescend to notice Henry Chan.”

Offering John Quincy a seat, Chan says, “Condescend to sit

on this atrocious chair.”

Such self-deferential statements are typical from Charlie’s

lips and occur throughout the novels.

Charlie Is a Family Man

It seems not to have entered John Quincy’s mind that Chan

could be a married man with a family until we read in chapter XVI:

|

"Here on gleaming sand I first regard my future wife," continued Chan. "Slender as the bamboo is slender, beautiful as blossom of the plum—" "Your wife," repeated John Quincy. The idea was a new one. "Yes, indeed." Chan rose. "Recalls I must hasten home where she attends the children who are now, by actual count, nine in number." |

Perhaps this is a slight miscount of the number of children

who occupy the Chan household.

The Chinese Parrot

indicates that there are ten children

in Chan’s family. In The Chinese Parrot,

chapter XI, Chan says, “I picture my humble house on Punchbowl Hill, where

lanterns glow and my ten children are gathered round.”

Behind That Curtain

reveals that Chan’s wife is expecting their eleventh child when, in chapter II,

Chan reflects, “Man—what is he? Merely one link in a great chain binding the

past with the future. All times I remember I am link. Unsignificant link

joining those ancestors whose bones repose on far distant hillsides with the

ten children—it may now be eleven—in my house on Punchbowl Hill.”

Prejudices of the Times Are Reflected in the Story

Mystery novels often reflect the lifestyles, attitudes, and biases of people who lived during the time written about. Gender and racial bias as well as “class consciousness” is reflected in the thoughts and behavior of characters in this novel.

Although Earl Derr Biggers endeavored

to overcome negative and misrepresentative stereotypes about Chinese people

during this period of history, some erroneous (and offensive) descriptions

slipped through his pen, such as Biggers’s depiction of Charlie’s “slant eyes”

in some passages or the reference to a Japanese man in chapter XX as “the Jap.”

Some characters do learn,

however. Miss Minerva begins with a prejudice, for example, as expressed in the

passage from chapter VII below (and which shows Charlie’s polite response):

|

Miss Minerva faced Chan. "The person who did this must be apprehended," she said firmly. He looked at her sleepily. "What is to be, will be," he replied in a high, sing-song voice. "I know—that's your Confucius," she snapped. "But it's a do-nothing doctrine, and I don't approve of it." A faint smile flickered over Chan's face. "Do not fear," he said. "The fates are busy, and man may do much to assist. I promise you there will be no do-nothing here." He came closer. "Humbly asking pardon to mention it, I detect in your eyes slight flame of hostility. Quench it, if you will be so kind. Friendly cooperation are essential between us." Despite his girth, he managed a deep bow. "Wishing you good morning," he added, and followed Hallet. Miss Minerva turned weakly to Amos. "Well, of all things—" "Don't you worry about Charlie," Amos said. "He has a reputation for getting his man. Now you go to bed. I'll stay here and notify the—the proper people." |

Miss Minerva is also prejudiced by what she considers the

slow investigation techniques of the island’s police detective force, which she

compares unfavorably with the Boston detectives.

But Minerva’s attitude toward Charlie eventually changes for

the positive. In chapter X, Biggers writes:

|

"I have it," she announced triumphantly. "The evening paper of Monday, June sixteenth—the one Dan was reading the night he wrote that letter to Roger. And look, John Quincy—one corner has been torn from the shipping page!" "Might have been accidental," suggested John Quincy languidly. "Nonsense!" she said sharply. "It's a clue, that's what it is. The item that disturbed Dan was on that missing corner of the page." "Might have been, at that," he admitted. "What are you going to do—" "You're the one that's going to do it," she cut in. "Pull yourself together and go into town. It's two hours until dinner. Give this paper to Captain Hallet—or better still, to Charlie Chan. I am impressed by Mr. Chan's intelligence." |

Later, Miss Minerva expresses her favorable impression to

Chan himself when she says, in chapter XXIII, “I congratulate you. You've got

brains, and they count.”

Charlie's Technique

Charlie

doesn’t seem to rely only on physical evidence. He often utilizes a

psychological approach.

|

"Have you formed any theory about the crime?" John Quincy asked. Chan shook his head. "Too early now." "You have no finger-prints to go on, you said." Chan shrugged his shoulders. "Does not matter. Finger-prints and other mechanics good in books, in real life not so much so. My experience tell me to think deep about human people. Human passions. Back of murder what, always? Hate, revenge, need to make silent the slain one. Greed for money, maybe. Study human people at all times." |

Chinese "Are Psychic People," Says Charlie

Another concept carried throughout the novels is that

Chinese are psychic. This may partly account for Charlie's intuitive approach to crime solving. In chapter X:

|

"I understand," John Quincy said, "that you've been rather successful as a detective." Chan grinned broadly. "You are educated, maybe you know," he said. "Chinese most psychic people in the world. Sensitives, like film in camera. A look, a laugh, a gesture perhaps. Something go click." |

Humor

There are some good, humorous lines in the book, but since we are running out of space I will share just one or two.

- In chapter XVII, Carlota Egan says to John Quincy Winterslip, “I was just figuring my pay-roll. You know, we've no undertow at Waikiki, but all my life I've had to worry about the overhead."

- Minerva describes a woman as “a self-made

widow.”

Charlie Chan Aphorisms

Charlie Chan’s aphorisms have become a major delight for

fans of the series, and a number of people have collected them from various

sources. These have become prevalent particularly in the movies. In this first

Charlie Chan novel I can only remember coming across one Chinese saying as

expressed by Charlie’s son Henry in chapter XIX: “Quoting old Chinese saying, a

picture is a voiceless poem."

Who Actually Solves The Case?

In the end, Charlie Chan and John Quincy Winterslip solve

the case independently but simultaneously. They discuss it in chapter XXIII:

|

They filed out. . . . In the anteroom Chan approached John Quincy. "You go home decked in the shining garments of success," he said. "One thought is tantalizing me. At simultaneous moment you arrive at same conclusion we do. To reach there you must have leaped across considerable cavity." John Quincy laughed. "I'll say I did. It came to me to-night. . . . “ "A brave performance," commented Chan. "But as you can see, Charlie, I didn't have an iota of real evidence. Just guesswork. You were the one who furnished the proof." "Proof are essential in this business," Chan replied. "I'm tantalized too, Charlie. I remember you in the library. You were on the track long before I was. How come?" |

|

Since I want to avoid giving spoilers I will skip to the end

with Minerva and John Quincy Winterslip getting in a car. Biggers writes, “John

Quincy started the car and slipping away, they left Charlie Chan standing like

a great Buddha on the curb.” |

Click Image to Click the image below to |

For more information about Charlie Chan, click on the links below to read articles.

The Novels by Earl Derr Biggers:

- The House Without a Key

- The Chinese Parrot

- Behind That Curtain

- The Black Camel

- Charlie Chan Carries On

- Keeper of the Keys

Charlie Chan Movies

- The Early Charlie Chan Films

- Enter Warner Oland: "Charlie Chan Carries On" and "Eran Trece"

- "The Black Camel" and Three Lost Charlie Chan Movies

- Charlie Chan's Aphorisms and Sayings

- Charlie Chan's Family as Described in the Books

- Charlie Chan's Family as Seen in the Movies

- Charlie Chan's Travels

Charlie Chan Pastiches

Amazon and the Amazon logo are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.

(This is a link through which I make a small commission if you buy. See here for more details.)